Erney Hersman is dead and the world is now a darker place. The call came in earlier this month, the ringing penetrating my dreams at four o’clock in the morning, and I waited a beat before I picked up the receiver. It was the night nurse at the rest home where Erney had been for over a year. “It was another stroke,” she said. “He passed peacefully”. Erney and I lived together for 50 years—yes, 50 years—and, since that call, I have been thinking about all that has transpired over those five decades.

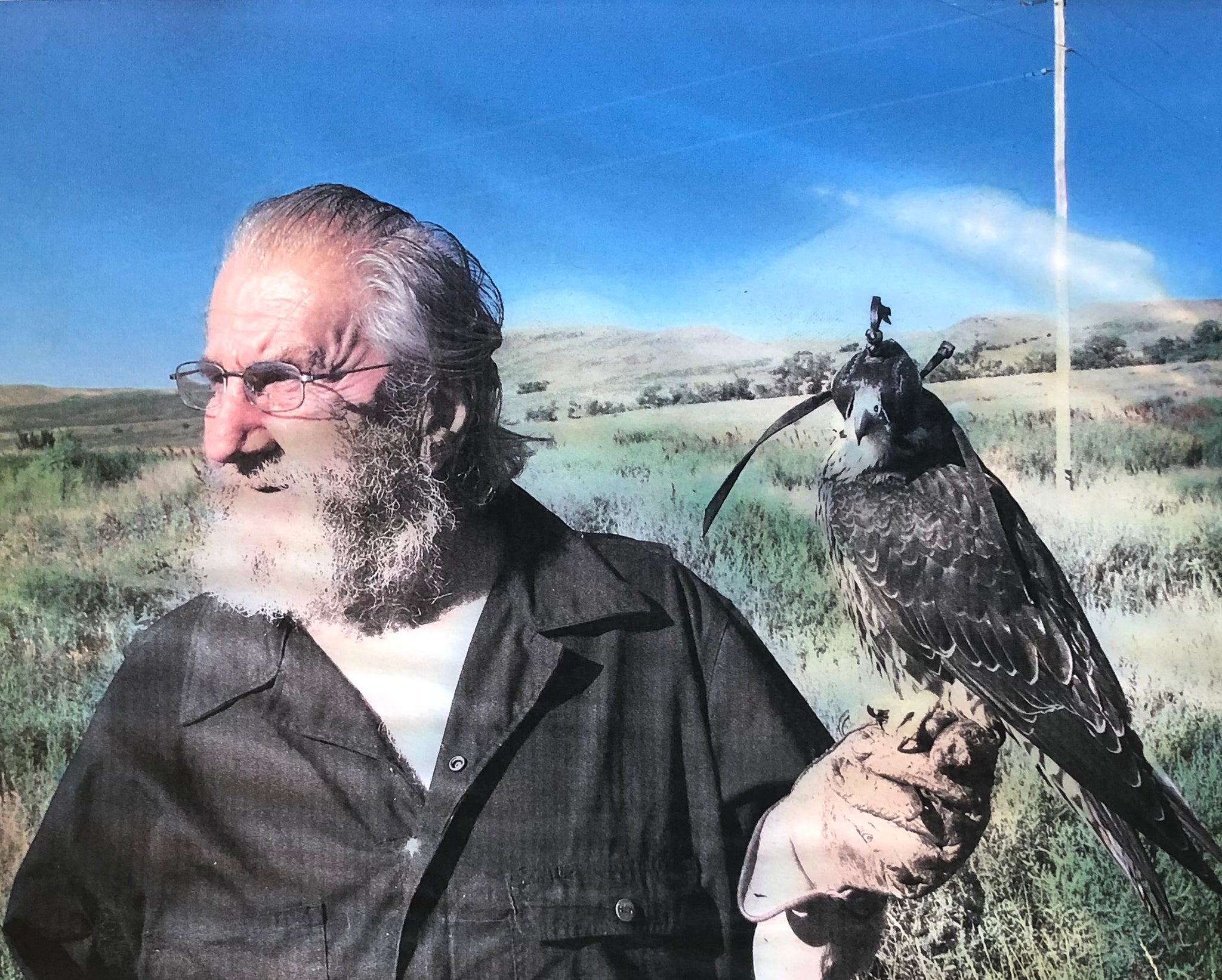

I met Erney in the fall of 1970, when I was a first-year graduate student at the University of South Dakota and he was working for the South Dakota Highway Department. We were brought together by a meeting of falconers who were advising the Game, Fish, and Parks Department on state regulations for the practice of falconry. I was 22 and he was 34. I’d come from a middle-class family in urban Ohio and had a little education behind me; his father had died when Erney was an infant and he was raised by a single mother in a large, rural family. His education was a high school diploma and he walked with a limp from a construction accident. I would learn later that Erney had refused care on a broken femur, a harbinger of a personality trait that led him to scoff at safety precautions. But I would also learn that he was gentle and kind, with a wealth of practical knowledge about animals, plants, and all living things. I would also learn that I, compared to Erney, was green as the prairie grass. We were something of an odd pair and shared only a love of the outdoors, a love of books, and falcons. But we bonded soon after that meeting in the autumn of 1970. Maybe we recognize that we needed each other.

By the next summer we had obtained a small acreage with a derelict house with broken windows, a jungle for a yard, old wiring, and no indoor plumbing. There was no well on the property, just a leaky cistern under the kitchen with mice floating on couple feet of fetid water. I had no idea how to make the house livable, but Erney did. He commuted 25 miles each way to his job in Yankton, South Dakota—every afternoon bringing water pipes, shingles, lumber, panes of glass, and even a toilet on his motorcycle. Driven by the certainty of a looming winter, we worked on the house in the evenings. He seemed to know just how things had to go together and was amazingly agile with his hands. He did 90 percent of all the work on the house, slow but steady as the days cooled into November. We heated the house with wood in an old potbellied stove. There was no television so we sat in the glow of a bare lightbulb to read. Erney’s reading list included a lot of natural history, African adventure, western Americana, and scientific books on butterflies, cactus, bromeliads, geology, and, of course, birds. He tutored me in the ways of the prairie, showed me how a human should relate to all the wonders of open spaces. More than any other man, he shaped me into the man I have become.

In that same poor light, he made all the leather falconry gear that we needed to outfit the falcons that we kept in that very living room—until the owner of the local shoe shop badgered Erney into taking over his pitiful business. So Erney quit his highway department job and began patching up the boots of farmers and the purses of their wives. But he could never bring himself to charge people enough for the repairs and did much of the work gratis. Of course, the shoe shop went bankrupt so he took a job on the neighboring ranch. Because Erney could do everything that a ranch needed, the rancher rode him like a rented mule. But Erney stuck it out and in the process taught me what to expect when the wind swung to the east, where pheasants made their nests, how to build a strong fence, and when the cranes would migrate overhead.

Finally, I got married and graduated with a master’s degree. My wife and I moved to the Black Hills and left Erney 300 miles behind. But a year later I got a call. Never a careful person, he had lost his right thumb to the power takeoff of a tractor. He had finally gotten enough of working long hours for short pay with no appreciation and he wondered if there was work in the Black Hills. My jobs took me away from home about half the time and there were chores on our little place that often went undone. I told Erney that I had lots of work and a spare bedroom, but no pay.

He showed up a week later in a beat-up Chevy Luv Truck with every single thing he owned in the back. He stayed for the next 45 years—first in a basement bedroom, then in a tiny cabin 75 yards from the house. As he had done with our first house, he did all the things that I didn’t have the skill or the time to do. The falcons were still a big part of our lives and he took care of them when I was on the road, even flying them to keep them in condition.

As he aged, his activities became more domestic. He built himself a greenhouse and taught himself to cultivate all sorts of rare plants. He kept chickens and developed ways to raise Hungarian partridge for release on our ranch. He became an expert on a unique agate found only in our area. And as he taught himself, I picked up some of the knowledge around the edges.

His cabin had electricity but he heated it with a wood stove. By then there was a television because his vision was growing too fuzzy for reading - though he could still see a falcon moving through the clouds at five thousand feet. But he sat in the poor light that he refused to improve and he tied thousands of tiny fishing flies to sell at the local fly shop. He rigged up a falcon perch and tamed the falcons with constant attention. Our falcons of that era, and the dogs that laid at his feet, were well versed in Gunsmoke, Big Time Wrestling, Andy Griffith, and the Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association Finals.

Then came the first stroke. He was found on the floor of the machine shop, conscious but terribly disoriented. There was some time in the hospital and a short stint in a rehab program. At our growing ranch, we were switching from raising cattle to raising buffalo and Erney wanted to help. I needed his intuitive understanding of animals but knew that things would not be the same. He still took care of the falcons in the off-season but Erney was no longer able to do much physical work. Being cooped up did not agree with him and he deteriorated until one morning I found him on the concrete floor of the falcon house. He had had his second stoke and lay on the floor, blinking his eyes. This time we called the sheriff and they came with an ambulance and took him away. For two years he bounced between the hospital and a couple of care facilities. But he never came back to the ranch.

One of the last times I saw him was through his nursing home window when he was recovering from Covid-19. The home had had an outbreak. He was suffering and wasn’t able to talk. I wouldn’t have been able to hear him anyway, so we stared at each other through the glass. The only flicker of the old Erney I saw was when he glanced at something over my left shoulder. When I turned to see what had caught his attention there was movement. It was a red-tailed hawk sitting in a tree a few hundred feet behind me. It was looking past me into the darkened sick room.

Covid-19 didn’t get Erney, but a final stroke did. Now, his ashes sit on the desk, watching lovingly over me. At the end of June, the few of us who knew Erney will take him out to the agate beds he knew so well. His ashes will nestle down among those ancient rocks and remain there forever.

Erney Hersman's Celebration of Life - Sunday, June 27, 2021

Erney's family and his ranch family gathered to celebrate his life.

They shared stories, went through old photos and then drove to his favorite agate bed on the ranch.

Here, his ashes were spread out – a beautiful place to rest and be free.

41 comments

I long to meet someone like him someday. Someone to teach me the things I didn’t know I loved. Thank you for your Storey.

Thank you, Dan. So glad to be one of the few who met Erney back at the Sturgis Broken Heart over a decade and a half ago a few times. Most special was that one time with son Cormac and the ranch tour by truck you sent the 3 of us on. We still have the candle holder he had turned and gave us. And getting to see his cabin and the falcon in the outbuilding that day was a bonus. If there was ever a true one of a kind, Erney was that….All best to you, Jill, Jillian, Colt, etc. Been too long between seeing you, but have at least 15 pounds of ground Wild Idea in my freezer from my Spring order—continuation of the good work y’all did and do.

Oh, Dan! What a beautiful goodbye. Thank you, I’ve wondered about Ernie too. Thank you again!!

I remember Erney from my early visits to the ranch. Thanks Dan for sharing. When I was young I too had a mentor who shaped my life in big ways.

Angela

R.I.P. Erney. I met him through the pages of “Wild Idea”, and will miss him. Thanks, Dan.

Tears in my eyes, what a beautiful friendship you shared – what a gift you were to each other. Love and hugs to you and the ranch family.

Your tribute brought tears to my eyes… Memories of Erney from “Buffalo for the Broken Heart” are in my head. He was a character that was so unique in the story. Very talented, and set in his ways. You were so fortunate to have him in your life. We all need characters to influence us and help us build ourselves. Thank you for sharing.

Dan, A beautiful and touching tribute to your life-long friend. Such loss and hurt first requires that there was a wonderful love and friendship. I know you will celebrate that for many, many days to come as simple things on the prairie trigger dear memories. Peace.

Just a few days prior we scatter my brothers ashes in the place in the Hills he loved so much. Your story was quite a tribute. Rest well Ernie.

Thank you so much for this post. After reading the Wild Idea books I’ve often wondered about Erney. Your love and respect for Erney showed through in your writing. And best of all, he looks exactly as I pictured him. Rest In Peace.

I never met him, Dan, but for as long as I’ve known you I’ve heard Erney stories. How lucky you were to have him in your life, and how sad you must be now. I am sorry. Aging is interesting, isn’t it?